What is “law and society” or the “sociology of law”?

My approach to mentorship and general advice for grad students can be found here. While I include lots of advice below, the linked document explains how I mentor students, my expectations for our interactions, and lots of advice for navigating grad school and academia. Even if you are not my student, you may find this document useful to compare (just see what another professor’s approach is) or to pick up different or additional advice to supplement your own mentorship (if there is a conflict, go with what your own advisor recommends since they will know more about your subfield, program, and trajectory and have their own style and expectations). My comments in a short talk on the hidden curriculum can be found here.

Book Recommendations. I love reading productivity and self-improvement books, as nerdy as that might sound. I’ve read a lot of them. Some are really terrible and quite unsociological (e.g., not recognizing the role of structure and putting everything on agency), but others are surprisingly useful. There are three books that I can’t recommend strongly enough; I think everyone who wants to get their shit together (and keep their shit together) should read them. They really helped me. What I like most about them is their concentration of actionable, high-impact advice. These are Arden’s Rewire Your Brain, Elrod’s The Miracle Morning, and Allen’s Getting Things Done. These three books are tied for first place. Each book occasionally says something cringy, but for the most part, I find them really useful.

At a second tier, I’d also add Willpower by Baumeister and Tierney and Originals by Adam Grant. These books contain some really helpful and practical insights, but I have some problems with them and they require a more critical read, which takes them out of my top tier. For one, they sort of come across as non-falsifiable (some of the conclusions they reach based on various examples aren’t necessarily what I would have thought, which feels a bit wishy washy). They also require a certain depth of attention–you can’t skim and look for highlights. For example, Grant uses the term “procrastination” to refer to taking a long time to actively work on a project, which is not how I would use the term, which I take to mean avoiding work on something and trying not to think about it, usually because it’s stressful and scary to think about… because I’m not working on it. This is an important distinction because he argues that the evidence suggests “procrastination” is good for creativity. I would say this is true if you mean working on a project well ahead of the deadline and thinking about it regularly, making small updates, continuing to brainstorm, for example while you read the literature or work on other projects. But if you read his advice to mean, it’s okay to wait until the last minute to work on something (like really wait to do any work or any productive thinking about it), yeah, that’s not going to help you. So be a careful consumer (as you always should be) because you can pull out very useful nuggets if you read carefully; I keep coming back to these books and finding truth in some of their insights.

As a third tier, there are a number of books that I found helpful but I can’t quite rank accurately: after a while, a lot of the advice is repetitive, too, so it depends on the order in which you read things—the first book that tells you a common piece of advice can be mind-blowing, but the second book will be less so, and these books are in that category. These books include Duhigg’s The Power of Habit (probably one of my most re-read books and a possible candidate for the top tier, but the terrain is just so common), Clear’s Atomic Habits (these two books overlap a bit, but both are very useful), Newport’s Deep Work (some of the advice is not terribly practical, depending on your socioeconomic status and family situation), Achor’s The Happiness Advantage, Branden’s The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem (I know, it’s a very self-help title, but this is a very practical book), and Tracy’s Eat That Frog (a lot of the best advice in this book has been cannibalized by other books; the Intro, Ch. 1-2, and 9-10 are the most useful, in my view).

I also really enjoy productivity and writing help books written for academics and occasionally for a broader audience. These are my favorites:

- Silvia’s How to Write A Lot (This book’s emphasis on tracking your writing and writing everyday are some of the key pieces of advice that you’ll see replicated in a lot of different places.)

- Schimmel’s Writing Science (This book formalized for me why I couldn’t understand what turned out to be bad writing, and helped me formalize a strategy for improving my own writing. I can’t recommend it enough.)

- Belcher’s Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks (I read this soon after becoming faculty, and the idea that you could write an article that quickly was mind-blowing and liberating. I don’t agree with all of the advice in there, but it is a great step-by-step guide for writing your first article, or your first article on your own as a solo author.)

- Zerubavel’s The Clockwork Muse (This book is really helpful for breaking down a big scary project into small bits and then sticking to a schedule to get it done. The idea of doing it this way is helpful, but in my experience, things often don’t go according to plan. So I like to incorporate these ideas for fungible tasks that I have to break up over a lengthy period like coding, or to try to give myself a general writing schedule, but without being too stuck to it.)

- Currey’s Daily Rituals (This book is not a traditional guide to productivity, but rather a series of stories about how productive creatives throughout history did their work; it was also turned into a series of Slate articles that looked at themes in their work styles.)

- Gallo’s Talk Like TED (This book is about how to give a good TED talk, but it’s been really helpful for thinking about how to write better and why certain strategies are so effective.)

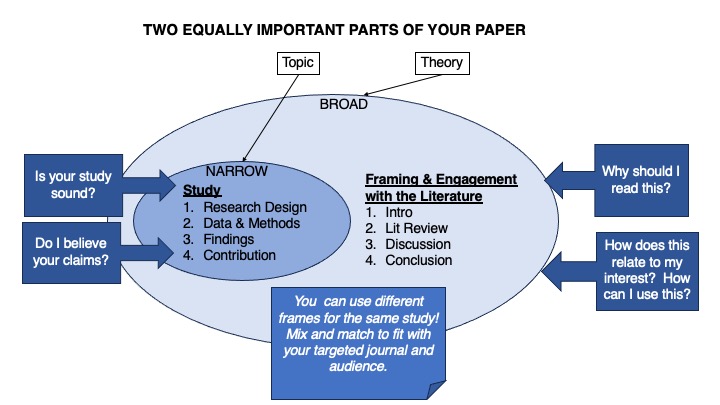

I have also written about writing and productivity. Ch. 4 of Rocking Qualitative Social Science is all about framing; the preprint version of that chapter is available here. My book in progress about writing and productivity, tentatively titled A Dirtbagger’s Guide to Writing and Productivity, is all about this topic. So far, my most useful chapter translates how to structure your journal article (other scholars have also written about this certainly, but I like my version, which is also customized with examples from my fields). A very simplified visual version of much of that advice is below:

Alt text and caption for the diagram: This diagram distinguishes between a narrow focus on one’s empirical study and the broad focus on how that study is framed for the literature. The narrow focus is on the research design, data and methods, findings, and contribution; these are the central focus to understand whether your study is sound and whether I believe your claims. The broad focus is on the introduction, the literature review, the discussion, and the conclusion; these sections tell me why I should read your paper/article; it does that by giving me some connection to see how it relates to my own interest so that I can think about how I might use your work in my own. Importantly, you can use different frames for the same study; you can mix and match the frame to the study, but choose the best frame for your targeted journal and audience.

And of course I love methods books! My favorite quantitative methods book is and always will be Angrist and Pischke’s Mostly Harmless Econometrics. For qualitative methods, there are a lot more options, especially recently. I cite a lot of useful works on qualitative methods (whether as examples of empirical scholarship or the advice on qualitative methods) in my book, but my favorite books are the ones that are fun to read, friendly books that make the work even more enjoyable. When I wrote the book proposal for Rocking Qualitative Social Sciences, the main “competitor” books (or rather books whose styles I was seeking to emulate) were Krista Luker’s Salsa Dancing into the Social Sciences and Howie Becker’s series of books on research, writing, case studies, and data. In the years during which I was writing or waiting for my book to come out, and soon after it came out, my book was joined by a host of other friendly guides to qualitative research. These books are listed in this twitter thread.

Reading Guide. Click here for a written guide on how to read academic, non-textbook books and articles that I prepared for my undergraduate students. While this document is intended for undergrads, graduate students might find it useful as well.

Video about how to read journal articles (and book chapters). Click here for a video explaining how to read academic, non-textbook books and articles that I prepared for one of my classes. (I recorded this when I had to cancel class one day because I was sick, so you can hear me getting stuffier over the course of the video (sorry!). There’s also a bit of stuff specific to my class, but it gives you a window into how I teach my classes. It picks up in between two other videos that set up the day and set up for next class.) Click here for the twitter thread version!

My Syllabi

- My grad course on penal change (SOC 638 American Punishment). This course is a tour of the punishment and society literature, focusing on the topic of penal change. It also explores various theories of historical change that might help us resolve some of the puzzles, controversies, and debates in the field. I sometimes think of this course as historical sociology meets punishment studies, but more interdisciplinary. The syllabus can be found here.

- My classic social theory meets punishment studies à la David Garland UG class (SOC 232 Introduction to the Sociology of Punishment). This course uses Garland’s Punishment and Modern Society to tour classic sociological theories and apply them to punishment and penal change, while also assessing the theories successes and limitations. The tentative syllabus can be found here.

- My introductory criminology/criminological theory UG class (SOC 333 Criminology). This course presents criminological theory historically, looking at how theories about what causes crime change over time. I tell my students: This class is not about what causes crime, deviance, or delinquency. This class is about what people think causes crime, deviance, and delinquency and where these ideas come from. We will review the standard theories about the causes of crime, the way in which crime is socially constructed and the many power relationships that contribute to this social construction. Finally, bringing these themes to the next level, we will study criminology as a knowledge production process (and what that even means). Since I’ve now changed this class to be fully online, with the readings linked in the course website, I can only post the brief schedule. But here’s an earlier version with author-year citations and links (although the links only work on UH campuses or through UH proxy servers).

- My organizational theory meets criminology and criminal justice UG class (SOC 337 Criminal Justice Organizations). This course introduces students to the study of major criminal justice organizations—police, courts, and prisons—through the lens of organizational theory. The organizational lens emphasizes the importance of on-the-ground, front-line actors like cops, attorneys, and prison guards in shaping actual decisions about how to carry out justice. The organizational lens demonstrates the effect of the organizational structure, the limited resources, and the need for legitimacy on organization-level decisions about policy and practice. Finally, the organizational lens examines the interactions, mutual influence, and competition between government, interest group, and criminal justice organizations that help initiate and sustain field-wide change. The first half of the course examines field-level or macro developments, especially trends in penal policies and technological innovation. The second half of the course examines what happens inside the organization and why. Each half presents aspects of organizational theory derived from sociologists examining other types of organizations before we delve into criminal justice examples and apply these theories. The central thesis of the course argues that prisons, police departments, and courts are organizations, and, consequently, to understand these places, we must recognize their organizational characteristics and tendencies: understanding these agencies as organizations is necessary for understanding their behavior. A sample schedule can be found here. I’ve taught different versions of this course over time, so if it’s useful to see how the course has evolved (mostly focused on covering more material in more detail and necessarily cutting out other interesting material), some earlier examples are my 2015 version (from FSU) and my 2017 version (from Toronto).

- My (newer) UG law and society course syllabus (SOC 332 Sociology of Law). While thinking about how to convert my regular law and society class to the online world, I decided to completely start fresh. My new syllabus contains articles from Law and Society Review (later versions will include LSI and other journals, but for now, there were already just so many to choose from in LSR alone) from the last four years. I reviewed each issue and came up with six topics that seem to be recurring themes and also map onto recognizable social problems: policing and racism, immigration and xenophobia, gender inequality, the environment and climate change, recognizing people with disabilities, and mass incarceration. (This not an exhaustive list, nor is it the set of the most common topics in LSR, although I’d say policing and immigration were certainly among the most popular topics–but there were many more law-focused articles, e.g., on lawyers, matters of jurisprudence, etc.) The class starts with the recognition that the world is kind of a mess right now and the law is at the center of that mess—bad law, ignored law, misbehaving lawmakers and law enforcers, etc. Can the field of law and society help us make sense of this mess or maybe even help us get out of this mess? I honestly don’t know the answer to that question, but we’re going to try. But to answer that question, we need to first figure out what is law and society. The field has expanded so extensively in recent years, which is a wonderful thing, but it doesn’t necessarily map onto the old canon. So this class tries to inductively figure out what law and society means today, based on what gets published in its flagship journal (an imperfect process, for sure, but one interesting window into the field). The reading list can be found here. My earlier law and society syllabus, which was more intentionally crafted around classic and newer important works, can be found here.

- My prison sociology UG classes. I’ve been wanting to teach a class on prison sociology, prison ethnography, or resistance more generally for a while, so I have multiple versions of these syllabi, but I finally get to teach a version of this class in SOC 431 Advanced Criminology and Delinquency. I’m still working on finalizing my syllabus for the fall. Here is an older draft of that class. Additionally, I have two syllabi for reading groups (both reading lists need to be updated as they are several years out of date, but that’s how it goes). Here is the reading list for recent prison ethnographies (keep in mind the relevant literature has virtually doubled since I put this together in 2015) and here is a reading list for a reading group of resistance in the prison context.

- My punishment and society UG classes (SOC 432 Punishment & Society). I’ve taught different versions of this class since 2011. Here is the first version, complete with the study guide and final test essay prompt. Here is a very early version from 2014. Since I’ve converted this to a fully online and asynchronous course with a lot more small readings, I do not have a complete reading list (it’s all embedded in the course website), but you can find the topics here.

- My prison history UG course (SOC 438 Prisons). I like to teach classes taking a tour of prison history in the US (one day I hope to do a course touring prison history around the world). I’ve created the UG version of this course specifically for the online asynchronous environment. The syllabus can be found here. I’ve previously taught a version of this course at the graduate level, the syllabus for which can be found here.

- Note: I’ve tried to strip out all or most of the course and university policies from these syllabi so it’s just the content of the course. (The actual syllabi are necessarily much longer and bureaucratic….)

Disciplinary Identity Issues. Click here for an introduction to a series of responses from leading scholars responding to the issues embedded in the question, “Are you a Criminologist or a Sociologist?”

Conferencing when Socially Awkward and Anxious. Click here for a short thread with tips for navigating an academic conference and some of the unspoken etiquette. (Note: This may have changed during/following the pandemic.) I also include other advice on conferencing in my above-mentioned mentorship document.

Qualitative Social Science: A Crash Course. Click here for slides from my multi-day workshop offering an introductory overview of qualitative methods (a “crash course”) for an interdisciplinary social science audience (based on my book, Rocking Qualitative Social Science). (Last updated October 26, 2022.) I’m more than happy to give this talk live; email me if you are interested!

Click here for an outline of the workshop (for workshop participants, in case you want to use the outline to structure your notes). (Last updated October 29, 2022.)

Click here for my short overview covering what I see as the major highlights from my book. (Last updated October 21, 2021.) I’m more than happy to give this talk live; email me if you are interested!

Historical and Archival Research: An Overview. Click here for slides from my 1.5 hr overview of how to do archival and historical research. (Last updated April 27, 2021.) I’m more than happy to give this talk live; email me if you are interested!

Click here for a twitter thread with some of the highlights from this lecture.

Advice on How and When to Try to Reform Your Department: The standard advice, for good reason, is wait until after tenure. Years ago, I was asked this question and gave a less conservative answer of “Don’t try anything in your first three years.” The group of students looked at me like I had completely lost their trust and I was part of the problem. I get it. But experience and research are with me on this. In your first three years, you are “too new” for people to take you seriously–they don’t know you well enough, they may not trust you, and they will be used to people coming in and trying to change things before the new person even understands the norms and practices and reasoning for them. Even asking questions about why things are done a certain way can lead to terrible pushback while suggesting a useful podcast can get your head bitten off by a senior faculty member. You also need to understand the best way to push for a particular policy or change and how to frame it in the most effective way–that is, to get the most support for it. For discussions of how to introduce change and build coalitions in your department (or university), first read Ch. 3 and Ch. 5 in Adam Grant’s Originals (on the theme of working from the inside and the need to first gain status before you try to exert influence) and then Ch. 7 in Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit (on the theme of making new, different ideas familiar), but Part II generally of Duhigg’s book will be useful. Ask yourself: are you more interested in actually making change–making your department or university or whatever organization better–or are you more committed to the fight regardless of the outcome?

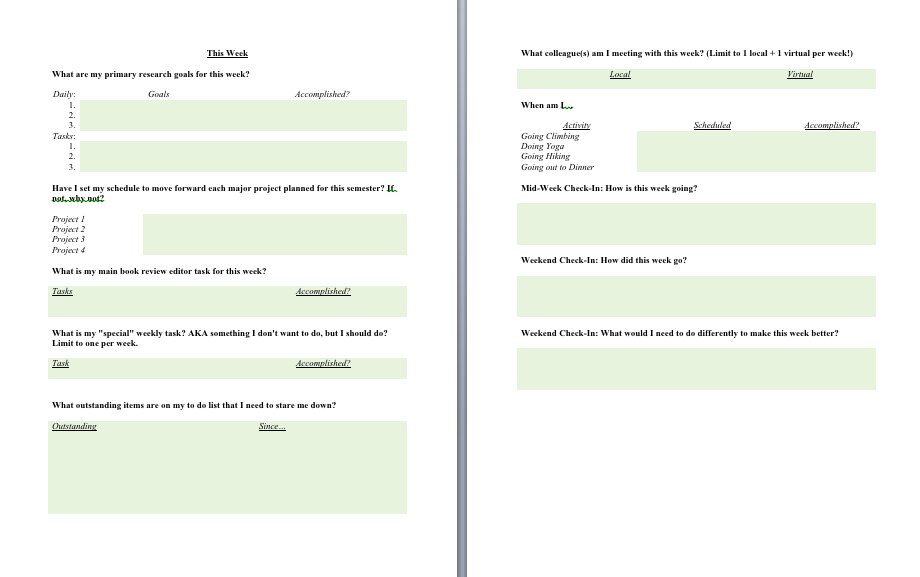

Weekly Planning. A plethora of productivity gurus, from David Allen (author of Getting Things Done) to Kerry Ann Rockquemore (creator of the Faculty Success Program), advocate having weekly planning meetings. These meetings (usually held on Friday, Saturday, or Sunday) encourage you to conscientiously think about everything you have to do and make a concrete plan for making progress on your goals. I rotate through a variety of weekly to do lists, but I recently developed a new template that builds in my personal, professional, and research goals that I especially like so I’m sharing it here. I’ve tweaked it to identify all the things I want to keep track of.

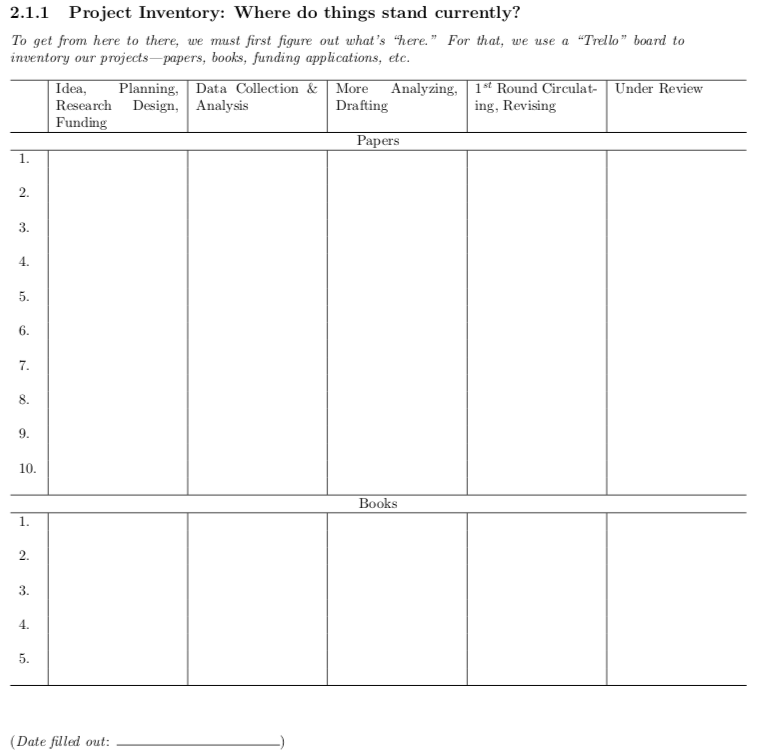

The Professor’s Planner. Because I got fed up with updating my bullet journal, and I didn’t like my word templates, I went ahead and made a full planner. It’s nothing you haven’t seen before, but just adapted for researchers who teach. Since my previous templates were helpful, I made it general enough for a broader audience (of faculty, although grad students and postdocs may also find it useful) and am posting it along with instructions. The idea is to print out the entire document and then reprint some pages as needed. This is version 1.5. I’d love to hear your feedback so I can tweak the next version!

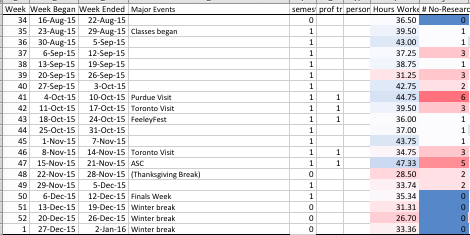

Productivity Tracking. If you are interested in tracking your time, this is the template spreadsheet I use (updated July 31, 2019). I track everything: my emails, my exercise/health goals, service, teaching/mentorship, and various research project. (I also keep track of what’s going on that week so I can also give myself a break if other things are interfering with my work.) I track my time down to the minute, but you can choose your own strategy. The used/filled-in version looks something like this:

In addition to looking for patterns in the data about which projects I’m ignoring, I also do weekly summary analyses. I track how much time I spend working each week and how many days I did not work on research.

I got the idea from Paul Silva’s How to Write a Lot, but I take it a bit further and track more than my research/writing time because I find teaching, service, and other work is important for my research and isn’t always clearly distinguished. So I aim for balance.

I track my time for many reasons, but I also agree with Theresa MacPhail that “productivity is overrated.” I write about these issues in a chapter on productivity in a sequel to Rocking Qualitative Social Science, or book 4, the in-progress book on writing and productivity.