This page contains my book recommendations (and some additional advice) on writing, productivity, and methods–topics that are near and dear to my heart. If you’d like to see my bite-sized advice from my twitter archive, check it out here.

I love reading productivity and self-improvement books, as nerdy as that might sound. I’ve read a lot of them. Some are really terrible and quite unsociological (e.g., not recognizing the role of structure and putting everything on agency), but others are surprisingly useful. There are three books that I can’t recommend strongly enough; I think everyone who wants to get their shit together (and keep their shit together) should read them. They really helped me. What I like most about them is their concentration of actionable, high-impact advice. These are Arden’s Rewire Your Brain (don’t be scared off by the really technical first chapter on the brain), Elrod’s The Miracle Morning, and Allen’s Getting Things Done. These three books are tied for first place. Each book occasionally says something cringy, but for the most part, I find them really useful.

At a second tier, I’d add Nerurkar’s The 5 Resets and Morgenstern’s Time Management from the Inside Out. Both are helpful for addressing burnout and they both offer concrete steps that you can take right now or start implementing right now. (I have only recently read these books, so I need more time to assess their impact, but they may move up to the first tier.) These are particularly useful books for us to read as we try to reset our work routines following the various changes we experienced during the pandemic. Many of us not only got burned out but also developed bad habits and generally lost our ability to focus for long periods of time that had previously helped us get shit done and feel on top of our shit, which in turn helped us stave off burnout and offered a buffer against some mental health challenges. For many of us, that buffer was destroyed and we got super burned out and overwhelmed and now we’re just plain struggling to regain our footing. These books offer helpful advice for building back our confidence in our ability to get shit done by regaining our focus and restoring our balance.

Also on the second tier is Sutherland’s Scrum; this is an excellent overview of the scrum (iterative/agile development) model, and a fun read, but I put it on the second tier because the applications are going to be more useful for some folks than others. If you work in research groups, teams, or committees, scrum is a really useful model (academia does not lend itself to scrum, which may be one of our problems). I’m still in the process of adapting scrum to my own workflow, focusing on two-week sprints and narrowing my focus, which is something that had also worked great for me in the past. A big challenge for us as academics to incorporate scrum into our workflow is we don’t have the luxury of a single-minded focus, balancing as we do our own research, collaborative research, teaching, mentorship, and departmental, university, and field service, email, administrative tasks/paperwork, and long-term planning. So my tweak is to only apply scrum to my research tasks: in theory, I have one hour a day to spend on research (during the semester, or 3 during break); so my scrum is set to what I can do in two weeks of one hour a day. That said, scrum can be applied to other aspects of our work—it’s just that research tends to be the one where we need the most help.

At a third tier, I’d also add Willpower by Baumeister and Tierney and Originals by Adam Grant. These books contain some really helpful and practical insights, but I have some problems with them and they require a more critical read, which takes them out of my top tier. For one, they sort of come across as non-falsifiable (some of the conclusions they reach based on various examples aren’t necessarily what I would have thought, which feels a bit wishy washy). They also require a certain depth of attention–you can’t skim and look for highlights. For example, Grant uses the term “procrastination” to refer to taking a long time to actively work on a project, which is not how I would use the term, which I take to mean avoiding work on something and trying not to think about it, usually because it’s stressful and scary to think about… because I’m not working on it. This is an important distinction because he argues that the evidence suggests “procrastination” is good for creativity. I would say this is true if you mean working on a project well ahead of the deadline and thinking about it regularly, making small updates, continuing to brainstorm, for example while you read the literature or work on other projects. But if you read his advice to mean, it’s okay to wait until the last minute to work on something (like really wait to do any work or any productive thinking about it), yeah, that’s not going to help you. So be a careful consumer (as you always should be) because you can pull out very useful nuggets if you read carefully; I keep coming back to these books and finding truth in some of their insights.

As a fourth tier, there are a number of books that I found helpful but I can’t quite rank accurately: after a while, a lot of the advice is repetitive, too, so it depends on the order in which you read things—the first book that tells you a common piece of advice can be mind-blowing, but the second book will be less so, and these books are in that category. These books include Duhigg’s The Power of Habit (probably one of my most re-read books and a possible candidate for the top tier, but the terrain is just so common), Clear’s Atomic Habits (these two books overlap a bit, but both are very useful), Newport’s Deep Work (some of the advice is not terribly practical, depending on your socioeconomic status and family situation), Achor’s The Happiness Advantage, Branden’s The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem (I know, it’s a very self-help title, but this is a very practical book), and Tracy’s Eat That Frog (a lot of the best advice in this book has been cannibalized by other books; the Intro, Ch. 1-2, and 9-10 are the most useful, in my view).

Finally, I add the excellent book Outlive by Attia. This book sits outside of my rankings because it’s about health, which is tied to our productivity in various ways, but this book is less about getting your shit together and how to be healthier, really. (There are so many shitty books out there on health, especially diets and exercise; this one does a really good job of not being one of those books. Even so, I feel torn about recommending a straight up health book. However, to the extent this book is also about feeling better, physically and mentally, it counts as a productivity book in my view.) I’ve read it multiple times because it’s so good and because it can be a bit technical and detailed.

I also really enjoy productivity and writing help books written for academics and occasionally for a broader audience. These are my favorites:

- Silvia’s How to Write A Lot (This book’s emphasis on tracking your writing and writing everyday are some of the key pieces of advice that you’ll see replicated in a lot of different places.)

- Schimmel’s Writing Science (This book formalized for me why I couldn’t understand what turned out to be bad writing, and helped me formalize a strategy for improving my own writing. I can’t recommend it enough.)

- Belcher’s Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks (I read this soon after becoming faculty, and the idea that you could write an article that quickly was mind-blowing and liberating. I don’t agree with all of the advice in there, but it is a great step-by-step guide for writing your first article, or your first article on your own as a solo author.)

- Zerubavel’s The Clockwork Muse (This book is really helpful for breaking down a big scary project into small bits and then sticking to a schedule to get it done. The idea of doing it this way is helpful, but in my experience, things often don’t go according to plan. So I like to incorporate these ideas for fungible tasks that I have to break up over a lengthy period like coding, or to try to give myself a general writing schedule, but without being too stuck to it.)

- Currey’s Daily Rituals (This book is not a traditional guide to productivity, but rather a series of stories about how productive creatives throughout history did their work; it was also turned into a series of Slate articles that looked at themes in their work styles.)

- Gallo’s Talk Like TED (This book is about how to give a good TED talk, but it’s been really helpful for thinking about how to write better and why certain strategies are so effective.)

- Truss’s Eats, Shoots, and Leaves (I always struggled with grammar as a kid and throughout college, but this book, combined with learning other languages, helped things to finally click for me)

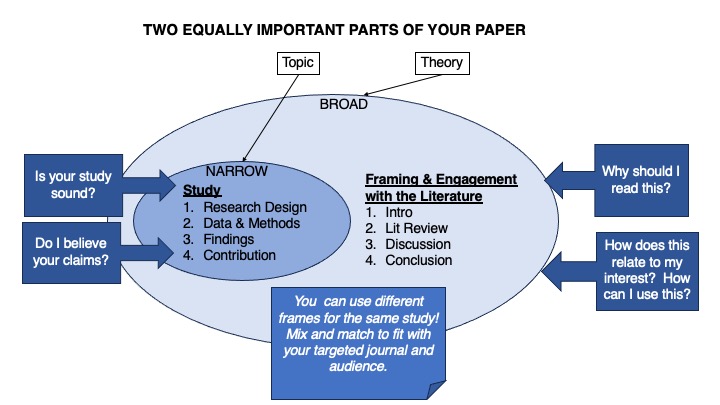

I have also written about writing and productivity. Ch. 4 of Rocking Qualitative Social Science is all about framing; the preprint version of that chapter is available here. My book in progress about writing and productivity, tentatively titled A Dirtbagger’s Guide to Writing and Productivity, is all about this topic. So far, my most useful chapter translates how to structure your journal article (other scholars have also written about this certainly, but I like my version, which is also customized with examples from my fields). A very simplified visual version of much of that advice is below:

Alt text and caption for the diagram: This diagram distinguishes between a narrow focus on one’s empirical study and the broad focus on how that study is framed for the literature. The narrow focus is on the research design, data and methods, findings, and contribution; these are the central focus to understand whether your study is sound and whether I believe your claims. The broad focus is on the introduction, the literature review, the discussion, and the conclusion; these sections tell me why I should read your paper/article; it does that by giving me some connection to see how it relates to my own interest so that I can think about how I might use your work in my own. Importantly, you can use different frames for the same study; you can mix and match the frame to the study, but choose the best frame for your targeted journal and audience.

And of course I love methods books! My favorite quantitative methods book is and always will be Angrist and Pischke’s Mostly Harmless Econometrics. For qualitative methods, there are a lot more options, especially recently. I cite a lot of useful works on qualitative methods (whether as examples of empirical scholarship or the advice on qualitative methods) in my book, but my favorite books are the ones that are fun to read, friendly books that make the work even more enjoyable. When I wrote the book proposal for Rocking Qualitative Social Sciences, the main “competitor” books (or rather books whose styles I was seeking to emulate) were Krista Luker’s Salsa Dancing into the Social Sciences and Howie Becker’s series of books on research, writing, case studies, and data. In the years during which I was writing or waiting for my book to come out, and soon after it came out, my book was joined by a host of other friendly guides to qualitative research. These books are listed in this twitter thread.