Although the field is increasingly popular, a lot of people—students and faculty a like—don’t know what “law and society” (or the “sociology of law”) means. While different scholars (both in the US and abroad) will have different ways of explaining this (I’ll get to that later), this is how I explain it.

Introductions

Law and Society is an interdisciplinary field, mostly of social scientists but also people from the humanities (and maybe beyond), studying the relationship between law and legal institutions, on the one hand, and society on the other. It’s an interdisciplinary (but mostly social science) approach to understanding law (writ large), laws (as in statutes and constitutions), legal decisions (which can also count as law), the application of law (such as through policing, regulation, the fourth branch of government administration, or by other actors in unexpected/everyday settings), legal institutions (like courts and prisons), and legal systems (individually or comparatively). Law and society scholars are especially interested in the law’s processes as well as its causes and effects (e.g., does a given law or reform or court case make a difference, why did that law get passed, how does a police department function, how do lawyers do their jobs and interact with clients, how do judges make decisions). But we also study how people interact with, use, think about, and experience the law and legal institutions, including how the law shapes people’s beliefs and behaviors but also how people creatively respond to the law and its underlying ideas and systems. Some scholars will say they study the law as an important social institution, meaning an important and long-standing area of society that structures, and is structured by, social life. Yet another way of saying all of this is we study “law in action.”

- Law and society is not standard law school fair. Confusingly, many law and society scholars are housed in law schools and have both JDs and PhDs. But when we distinguish law and society from standard law school fair, we are distinguishing law and society scholars from most (but not all) law professors. That’s because while traditional legal scholars study “law on the books” (legal doctrine or case law), law and society scholars study the “law in action” or law in society. Likewise, traditional legal scholarship tends to be “normative” (making “should” statements, grounding policy recommendations in logic, reason, and legal reasoning) while law and society scholarship tends to be descriptive and explanatory (often grounded in and extending our general knowledge of how the world works, but when there are policy recommendations, these recommendations are based on an analysis of data).

Importantly, Law and Society scholars (sometimes called sociolegal scholars, especially outside of the US) study the law in a way that most law professors and law students (aka legal scholars) don’t. (This is where we start to get into some pretty big differences between the US-dominated version of law and society and the types of law and society or sociolegal studies beyond the US, particularly in Canada and Europe, which tend to be anchored in law schools or those working in legal education.)

The “law in action” designation can be contrasted to “law on the books,” which is considered the domain of law schools. Law school crowds are interested in understanding what the law should be—how a given judge should interpret the law and decide a case—or what’s typically called “doctrinal analysis,” as in the analysis of legal doctrine (principles handed down over time through court cases and laws—at least in “common law” countries). Law and society was actually formed in response to that approach, with its origins in the Legal Realism movement of the 1920s and 1930s (Legal Realists called bullshit on the idea that judges just apply the law as neutral umpires; instead, they recognized that judges have their own preferences and biases that infused their judicial decision making). Like those early Legal Realists, Law and Society scholars are interested in questions like why do judges interpret laws in particular ways (rather than assuming they are just following the law), as well as questions like why do certain types of groups seem to always win their court cases, why do celebrated successful court cases for progressive social movements actually not have the impact that would merit such celebration, why don’t people go to court when they have a viable case (i.e., when they have been harmed/wronged), how do people make sense of court decisions, and so on. (These are just scratching the surface.)

At this point, many social scientists use social science theories and methods to study the law in action—for example, criminologists examine sentencing disparities, social movement scholars study various strategies activists use to get legal change, political scientists explore judicial decision making, policy scholars evaluate the impacts of various laws and policies or why some legislation gets adopted and not others, punishment scholars analyze the experience of people undergoing punishment, and legal historians study old court cases, laws, regulations, punishments, and how rules and rights played out in reality. But what makes something recognizably “law and society” and not just “law and social science” is the reliance on widely (within the field) recognized concepts and theories about how the law plays out in practice. Understanding these concepts and theories helps us avoid re-inventing the wheel every time we study the law and realize it isn’t quite what we or others naively expected.

Before I get to those important concepts, I want to distinguish between Law and Society and Law and Social Science. I would say that (at least in the US) there are two dominant views of Law and Society—the one that I’m describing and another view that understands Law and Society as kind of an umbrella term that just means any social science or humanistic investigation of the law. Basically, if your study has anything to do with the law or the legal system, it would count as Law and Society in their view. And there are folks within the traditional field of Law and Society who would agree with this view. It goes back to one of the defining features of our professional association (Law & Society Association, discussed below), which many of us describe as a “big tent”—all are welcome. It’s also taking the first prong of one of the defining features of Law and Society—how we distinguish ourselves from traditional legal scholars who do doctrinal work—and stopping there: any empirical analysis of the law. But at this point, there are distinct fields and subfields across the social sciences and humanities that most folks would say are not Law and Society—for example, law and economics, empirical legal studies, or criminology. These fields might overlap and there might be studies within these fields and subfields that are recognizably Law and Society, but the fields themselves are not Law and Society, and there’s no way to distinguish them from Law and Society if we just say we’re studying the law from non-doctrinal perspectives, or using social science or empirical methodologies to study the law. Each of these fields have core studies and their own “flavors”—questions that most in the field care about; theories, concepts, and literatures that one must engage to be taken seriously; methods of inquiry; styles of writing; even norms about how we organize our articles in peer-reviewed journals. A broad definition of Law and Society as any empirical investigation of the law bulldozes those very important differences that people in each of those fields care about. So as much as Law and Society is and should be a big tent (it’s better for the field when we get more people in it), I still think it’s useful to be clear about what makes it distinctive rather than just going with the Law and Social Science (or Law and Humanities) designation.

Some important concepts in law and society (but not limited to law and society) include: legality (everything law-like that isn’t technically law), the constitutive power of the law (how the law shapes our reality) and the mutually constitutive role of law in society (how law both shapes and is shaped by society), legal mobilization (how and when people use the law or their rights), legal consciousness (how people think about, experience, and understand the law), legal ambiguity (the unclear meaning of, and lack of definitions in, the law, whether a given statute or court ruling), legal pluralism (multiple legal systems in any given jurisdiction), legal endogeneity (how regulated organizations shape the very laws intended to regulate them), legal cynicism and legal estrangement (how people lose faith in the law/legal institutions and feel distance from it/them, and don’t use it/them), procedural justice (the legitimacy accorded to a legal process based on how one is treated, rather than the outcome or substantive justice), and adversarial legalism (the way in which American policies and people disproportionately use litigation and the threat of litigation, to deal with problems, rather than more centralized alternatives like government-led reform or informal solutions like mediation and negotiation).

Although they aren’t associated with nifty legal– jargon, many scholars are also interested in the perceived legitimacy of the law and legal institutions; how individuals, organizations, and other groups comply with or resist the law; how people operate outside the law, such as by bargaining in the shadow of the law or creating non-contractual agreements or simply relying on norms about appropriate behavior; the role of discretion, especially among front-line workers who apply the law; and law and “development” or particularly how legal actors from the Global North sought to impose certain types of legal systems on countries in the Global South (the “developing world”) to help them out (using their own understandings of help), often with unfortunate consequences (from the perspectives of both Global North and Global South actors). Law and society scholars also study lawyers, law firms/practice/clinics, law students, and law schools, but often with an eye to how their characteristics, the stratification in the profession and schooling, and training shape lawyers’ interactions with clients and the consequences for case outcomes or on access to justice. They also study legal institutions charged with carrying out criminal justice like police, courts, prisons, and parole/probation agencies, but often to an eye to the place of the law and employing the themes discussed above (and below), which distinguishes such studies of criminal justice from regular criminology, sociology, political science, anthropology, history, etc.

[Forgive my sketchy descriptions above, which are meant to be teasers rather than legitimate and adequate definitions.]

It’s important to emphasize that increasingly scholars outside of law and society are studying these concepts, but often in isolation from the rest of the law and society literature. For example, legitimacy, discretion, law and development, punishment, and the legal profession are all studied by other fields. Again, what really gives a study the “flavor” of law and society is often its engagement with other areas of law and society rather than studying a given topic in isolation. Indeed, studying these topics in isolation is a shape because there are also strong connections between law and society’s different theories, concepts, and areas of significant interest. Indeed, the lines between some of the theories, concepts, and subfields or subareas of law and society are super blurry and overlapping (an area for future research to help us figure this out). My very, very imperfect rendering of the field of law and society is badly drawn below (the image that looks like a conspiracy theorist went to town in powerpoint). It’s going to leave important things out, and I gave up on making all the arrows connect the appropriate boxes, but it’s a start. (I’d love to see it if someone has made a better one!)

Remember I said law and society folks study the “law in action” and law school folks tend to study “law on the books”? Probably the most foundational idea (and recurring finding since the early twentieth century) in law and society scholarship is what is known as “the gap between the law on the books and the law in action,” meaning the way in which statutes and court cases do not always (frequently do not) translate into practice. At this point, “the gap” is almost expected (although finding situations where it doesn’t exist is also interesting—basically, the law working exactly as intended is actually pretty surprising and therefore noteworthy), so our goal becomes to understand why and how it happens, especially identifying the mechanisms and conditions that make such outcomes possible. Indeed, much of law and society scholarship has already identified numerous mechanisms, some of which are highlighted above (e.g., legal ambiguity, legal endogeneity, discretion, various concepts in the literature on legal mobilization, the literature on lawyers, legal cynicism, etc.). However, some scholars dismiss the conventional “gap study” because of misplaced optimism that the law and legal system can actually make positive change, rather than replicating systems of inequality. Basically, some folks have said enough already: we keep finding problems with the law, so why do we think the law or legal reforms are the way to fix deeply rooted problems in society. (Critical legal scholars go a step further and says if the law is set up by the powerful, why should we expect the law to do anything but reify inequality in the first place? Likewise, critical race scholars say if the law is set up by white folks to protect white interests, we should always expect the law to be unjust toward non-white folks. One big difference between these two approaches, which are more dominant in law schools, and law and society is they start with the expectation and go from there, while the most critical law and society look to the repeatedly disappointing findings and make their expectations from there.) Either way, our attention to the gap foreshadows a kind of disappointment with the law and legal institutions, which characterizes much law and society scholarship over the decades.

When I took my first class on law and society, I cheekily summarized it as “Let’s enumerate the ways in which the law disappoints.” (Actually, I said, “…the ways in which the law screws people over.”) While there is more to it than that, that is a common theme in a lot of the empirical literature, as I hinted above. Said more concretely, much of the empirical literature on law and society reveals not just the ways in which the law doesn’t work as intended or expected, but actually goes so far as to replicate (or reify) social inequality. There are also other themes, however.

When I teach my law and society class, I typically organize it around three big questions or sets of questions:

- What is the law—or what do we mean by “law”? What does “law” look like across societies, and how can we recognize “law” when it does’t look like we might expect, especially from our Modern, Western ideas? Where does the law come from? Why do we have the legal systems we have? And how does law shape how people think or behave? (These might sound like very disparate big questions, but every time I try to split them up, they blend right back together, so I treat them as one unit.)

- Key concepts/theories: Classic Theories of Law (Natural Law v. Legal Positivism) and of Judicial Decisionmaking (Legal Formalism v. Legal Realism), Law v. Norms, Legality, Legal Consciousness, Legal Knowledge, Legal Socialization, Rights Consciousness/Rights Talk, Myths of Litigiousness, Adversarial Legalism, Law and Development, Policy Diffusion/Transfer, Legal Pluralism, Disputing Across Societies, Legal (and Penal) Change

- We draw extensively on anthropology, history, sociology, and political science.

- We are interested in the most micro levels of how individual people make sense of and understand the law to the most macro levels of comparing legal systems across time and place (country).

- Some Upshots: Law and society scholars recognize that each legal system is deeply shaped by a jurisdiction’s social context. But law and society scholars also understand the law to be so much broader than law on the books (statutes, court decisions). And law and society scholars understand that the law has a large impact on how people make sense of the world and think about themselves, even as these ideas are also shaped by broader factors in the social/cultural, political, and economic environment. (The readings and lectures fill in the why’s and how’s of all of this.)

- When do (or don’t) people use the law (claim their rights, file a grievance, talk to a lawyer, go to court)? Why don’t they use the law more often? Basically, what do people do when they experience “trouble”?

- Key concepts/theories: Contemporary Disputing (Pyramid/Tree of Disputes), Legal Mobilization (Naming, Blaming, and Claiming; Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law; Alternatives to Legal Mobilization), Resistance, Legal Capability, Access to Justice, Hierarchies in the Legal Profession (and their impact in practice), Procedural Justice, Legal Cynicism, Legal Estrangement, System Avoidance, Unexpected Claimsmaking

- We draw extensively on sociology, economics, history, early empirical legal studies, and psychology.

- We are primarily interested in micro-level interactions, but also set against a larger social context, as well as the meso-level with the interactions of groups and organizations, in relation to the micro-level decisions of individuals.

- Some Upshots: Law and society scholars find that people don’t use the law nearly as much as they could, and this is particularly true for the most vulnerable–those who arguably most need the law or whom the law is most intended to protect because they have been subjected to justiceable harms. While the reification of inequality is a huge theme, we also see other contextual reasons relating to cultural norms within various subgroups that resist using the law (even talking with lawyers) as well as strategic decisions by lawyers guiding negotiations once parties do engage representation. However, the work of legal historians also show how disenfranchised groups (especially women and African Americans) used the legal system to defend their own rights, offering a layer of contextual contingency to otherwise routine findings of under claiming. (The readings and lectures fill in the why’s and how’s of all of this.)

- What happens when people use or experience the law, especially the formal legal system (claim their rights, file a grievance, go to court, participate in a truth commission, experience policing and punishment)? What are the structural disadvantages of claimsmaking? What are the consequences of discretion and what shapes discretion?

- Key concepts/theories: Why do the Haves Come Out Ahead (also Repeat Player Advantage), Law and Social Change (aka what’s the impact of Supreme Court cases and social movements), Alternative Disputing Structures (ADR, IDR, Mediation), Legal Ambiguity, Discretion, Organizational Compliance (Symbolic Compliance, Loose Coupling, Cooptation, Judicial Deference, Legal Endogeneity), Legal Intermediaries/Legal and Other Professions’ Influence on Legal Interpretation/Compliance, Judicial Decisionmaking, Courtroom Workgroups (and other legal practice norms), Experiences with the Fourth Branch/Front-line Workers/Street-Level Bureaucrats, Transitional Justice

- We draw extensively on sociology, early empirical legal studies, organizational studies, history, policy administration, and political science.

- We are interested in the micro level of individual decisions and interactions, the meso level of organizations (courts, companies, schools, NGOs) interacting with each other, and the macro level of how social change at the national and international level interact with legal change and legal opportunities.

- Some Upshots: Law and society scholars find that the law often fails to achieve its stated goals or to function as expected (at least by its more idealistic proponents). Frequently, this finding is traced to structural factors, including resource/power disparities echoing some of the findings in the last section but often demonstrated at a larger or more systematic scale. But we also see the role of various professional norms and routines shaping both structural and interpersonal dynamics. Returning to some theories and concepts from the first section, however, we also find surprising pathways outside of the law to achieve the very ends the law had promised. (The readings and lectures fill in the why’s and how’s of all of this.)

As the upshots indicate, these questions map on to the ways in which the law is actually much more than we think of (e.g., statutes and court cases v. norms), how rarely people use the law and why, and the way in which the law typically doesn’t work the way we think it does (i.e., it often doesn’t live up to its promise or expectations, but sometimes it also does way more than we think it does). The key theme of my class was always that the law is both more and less powerful than we think it is.

Want a more concise, practical guide to why the law doesn’t work the way we think it does or should? Check out my Law and Society Cheatsheet.

So, to conclude: while there are a lot of different takes on what constitutes law and society or sociolegal studies, and there are a lot of different versions of law and society around the world, I’m focused on the version of law and society that originated in the United States (the one most associated with the LSA). This version of law and society has its roots in legal realism in the early twentieth century and has since expanded to become an international and even global field of scholarship. While the distinctive national and regional versions of law and society around the world are beginning to blur as academic research becomes more global, this version of law and society still retains its unique “flavor” because of its reliance on a certain collection of research questions, theories, and concepts. This version of law and society tends to distinguish itself from the normative doctrinal work popular in law schools and from approaches (more common in criminology, political science, and policy administration) that define law narrowly and mechanically; instead law and society scholars treat law as a social institution, study the law in action, or generally look at the social life of the law—how the law both shapes and is shaped by society. Because law and society scholars define law quite broadly–more than the black letter of legal statutes or court decisions–they include things that are law-like, but not technically law, hence our interest in norms, rules, regulations, and what people think the law is or what they experience as law. And law and society scholars use the tools of the various disciplines, especially the empirical methodologies and theories of the social sciences, to study the law in these ways. A key theme in the law and society literature is a recurring disappointment because the law doesn’t work as promised, leading to a general skepticism about the law’s ability to make a (positive) difference in society. More generally, law and society scholars tend to see the law as constrained by its place in society, but also as sometimes even more powerful than we think, but usually in ways that aren’t quite intended or expected.

- Many distinct law and society subfields exist, as do disciplinary variations of “law and society”!

You can get a taste of the many topics and subfields that exist by looking at the CRNs or collaborative research networks of the Law and Society Association. (My favorite is CRN 27 Punishment & Society!)

Moreover, as noted above, other disciplines have their own versions of how they study the law: e.g., Political Science has Public Law scholars who are like the law and society scholars of that field; historians interested in the law do Legal History, much of which combines the lessons of history and law and society; there are also Legal Anthropologists and folks who study Psychology and the Law. Criminology sort of has two relevant subfields: many scholars in that field study sentencing disparities, which is a classic interest of law and society, but since that topic is so well embedded in modern criminology, I’d say law and society has sort of ceded the topic and the vast majority of the action in that subfield takes place in criminology journals without referencing law and society scholarship. The real bridge between criminology and law and society is Punishment & Society, an interdisciplinary exploration of the relationship between punishment and society; I’d say P&S is more distinctly a subfield of law and society, but it includes many folks who attend criminology conferences, work in criminology departments, teach criminology, and self-identify as criminologists (among other academic identities), plenty of whom don’t attend LSA or identify as law and society scholars. There’s also an interdisciplinary field of empirical legal studies, or quantitative scholars (primarily) from law schools, economics, psychology, and political science who use very sophisticated research designs and statistical analyses to analyze various aspects of the law, usually with a heavier policy focus than a theoretical one. Last, but not least, the sociology of law!

The Sociology of Law is the subfield of sociology devoted to understanding the relationship between law and society (see everything above), but often through an explicitly sociological lens (even though a lot of the work is still pretty interdisciplinary, overlapping with criminology and political science, for example) or emphasizing things sociologists distinctly care about. Given the historical dominance of sociology on the field of Law and Society as well as the growing interdisciplinarity of all fields, however, it can sometimes be difficult to figure out the dividing line. For example, sociologists of law often connect their study to inequality and social marginality, but many law and society scholars are explicitly interested in how the law creates, reinforces, and exacerbates inequality and social marginality. Indeed, many of law and society’s most important articles were published in sociology’s leading mainstream journals (e.g., several articles by Laurie Edelman in the 90s, 00s, and 10s, but more recently also articles by Asad Asad and Caleb Scoville). As another example, a hallmark of a trained sociologist is knowledge of social theory, especially the trio of Durkheim, Marx (or Marxist theory, anyway), and Weber—and often we add in Foucault as an honorary fourth. But these folks were also very interested in law and legal institutions and so are also core to law and society (and often required reading for many intro law and society courses). The dividing line is pretty blurry given these overlaps. However, works of sociology of law typically try to speak to generalist sociologists, not just to law and society scholars, so they will often articulate their contributions to multiple sociological audiences, where people who study the law are only one such audience. (For a fascinating history of how the ASA Soc of Law Section came about, see this section newsletter from 2002 and the Soc of Law section website’s history page. For a great book on the sociology of law, see John Sutton’s (2001) Law/Society; in it, he defines the sociology of law as “an intellectual project in which empirical data are used to describe and explain the behavior of legal actors” (p. 14). This is a good definition, but it probably is too broad to be super helpful, since it still includes what folks do in political science or criminology. However, it’s good to have the comparison. I encourage folks to read his lengthier description in his book!)

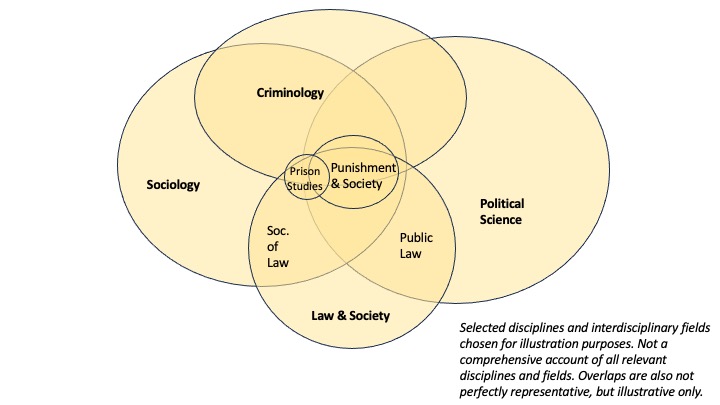

A Visual Might Help

I often describe the various overlapping fields and subfields with a complicated venn diagram. For illustrative purposes (and to not get to messy), I include only a few disciplines and subfields, including those most relevant to me (except history), but there are many others I could include. It’s a useful exercise to think through how your fields and subfields fit together, so if your fields aren’t represented below (first, please don’t feel left out! there is only so much space), try to map out how your fields would look using the figure below as a jumping-off point.

Professional Associations

The main professional home for US-based law and society scholars (but open to scholars in other countries) is the international Law and Society Association. (LSA isn’t just “open” to other scholars—more than a third of its membership comes from outside of the US, with folks coming from all inhabited continents!)

The main professional home for US-based sociologists of law (but open to scholars in other countries) is the Sociology of Law Section of the American Sociological Association.

Graduate students and junior faculty should especially consider joining both groups as both support a range of wonderful prizes for student papers, articles, books, and other achievements, not to mention venues in which to present your research and meet other law and society scholars. LSA also hosts an annual pre-meeting grad student and early career workshop that I highly recommend! Note: you don’t have to be a tried-and-true law and society scholar to join these groups! You can join to learn more!

There are other national and international law and society and sociolegal associations, some of which are regional (such as the Asian Law and Society Association) and others are national (such as the Canadian Law and Society Association or the (British) Socio-Legal Studies Association)!

Journals: To Learn More and/or Publish Your Research

The main (generalist) journals for US-based and much international law and society scholarship are Law & Society Review (the flagship journal of the Law and Society Association) and Law & Social Inquiry (the flagship journal of the American Bar Foundation, the research wing of the American Bar Association), but law and society research is often published in disciplinary journals as well. More specialized or subfield law and society journals include Studies in Law, Politics, and Society; Law and Policy; Law and History Review; Political and Legal Anthropology Review; Law, Culture, and Humanities; and Punishment and Society. You can read literature reviews on specific topics in the Annual Review of Law and Social Science. Additionally, there are law and society journals from other countries and regions, including the Asian Law and Society Journal, Canadian Journal of Law and Society, Journal of Law and Society, Social and Legal Studies, and others. (Note that there are different “law and society” literatures with different “canons” and expectations; these vary to some extent nationally, but also by the association they are associated with.) If you are interested in publishing in Law & Society Review, you should read this “From the Editors” note by its current co-editors. For some additional advice about how to structure social science journal articles with lots of examples about law and society journals, see this chapter from my book in progress, A Dirtbagger’s Guide to Writing and Productivity (a sequel to Rocking Qualitative Social Science).

A Bit More About Law and Society

Law and society was formalized in the Law and Society Association, an international organization founded and housed in the US, in the 1960s. They have a very nice description of the field and its basic principles or approaches:

The Law and Society Association is an interdisciplinary scholarly organization committed to social scientific, interpretive, and historical analyses of law across multiple social contexts. For sociolegal scholars, law consists not only of the words of official documents. Law also can be found in the diverse understandings and practices of people interacting within domains that law governs, in the claims that people make for legal redress of injustices, and in the coercive power exercised to enforce lawful order. Sociolegal scholars also address evasions of law, resistance and defiance toward law, and alternatives to law in structuring social relations.

(https://www.lawandsociety.org/about-lsa/)

Since there is a large literature (since about the 1950s and 1960s) helping us make sense of these things, if you study/write about law and legal institutions, it’s important to engage with that literature (engage = more than just cite, but also discuss, critique, extend, apply, etc.). In fact, in my view, what really makes scholarship today law and society scholarship is that it engages with the existing law and society literature (even while it might, and hopefully does, engage with other literatures). It’s that engagement that distinguishes something that is simply topically relevant studied through other fields’ traditions and lenses from something that is recognizably law and society (that engagement also prevents people from reinventing the wheel and allows them to use useful analytical frameworks). Much of the law and society literature can be found in articles from the list of journals above. To get a crash course in the field, you can read overviews of the field and then check out the articles and books they say are important.

For a list of excellent overviews of the field of law and society, see my curated list here. I’ve also posted my law and society syllabus on my syllabi page or click here.

- There are important international variations in the meaning of “law and society”!

Importantly, what exactly “law and society” means in other countries will differ. For example, living in Canada, I learned that many Canadian Law and Society scholars (who have their own association and their own journal) have a different flavor, with different methods, theories, topics, writing styles, and overall approaches. It is a distinct literature. (Then-graduate student, now UMSL assistant professor Katie Quinn and I empirically compared the leading journals for Canada and the (often called U.S.) law and society associations. Canadian law and society is much more pluralistic in its theories and methods, has truly distinct theoretical frameworks, and is generally focused on overlapping but different topics—for example, they are far ahead of us on studying Indigenous issues and colonialization.) When searching for a home to publish your research, it’s helpful to look at the research published by scholars associated within a given field, recognizing that these international differences exist. A really good trick is to look at the literature you are citing in your article—what journals published that work? It would be a good idea to send your work to the journals you cited the most because that’s a sign that you are engaging literature that journal (its editors, its reviewers, its readers) care about and would be open to publishing.

- Is law and society “critical”?

I want to return to a point I made above about law and society scholarship’s theme of disappointment with the law and legal institutions. This recurring disappointment contributes to a sense that much of law and society scholarship is “critical.” I’m using a little c here, because scholars do not necessarily set out to be critical (what I’d term Critical scholarship), but the reality has just led to so many findings that show the law’s failure. In fact, this is a good time to distinguish law and society from Critical Legal Studies and Critical Race Theory, movements which emerged in law schools a little after law and society—more specifically, CRT split from CLS (here’s a useful overview of that history). (Although today we mostly refer to them as literatures, they all started out as “movements” of scholars breaking away from law school’s doctrinal focus with a particular focus on how the law shapes class-, race-, and (later) gender-based inequalities.) These three movements overlapped a bit, particularly in the early years (although overlaps have waxed and waned and CRT in particular has become more popular since about 2016 and spread well beyond law schools, their long-time home). But it’s helpful to think of them as distinct. I think of CLS as more Marxist and explores the class biases of the law, while CRT focuses on the law’s racial biases. Law and society, which scholars often describe as a “big tent” field (in the sense that we try to include everyone in our club), tends to have a more general focus that explores all the forms of inequality shaped by and shaping law (both on the books and in action), but also not just inequality but all types of experiences with the law. I also tend to think of law and society as little-c critical and the other two movements as more intentionally Critical. Finally, law and society was historically more empirical and also quickly moved beyond law schools into the disciplines, with a heavy emphasis on social science methodologies; until recently, CRT was almost exclusively found in law schools (contrary to politicians’ claims that it was being taught in little kids’ schools) and has a complicated relationship with traditional social science methodologies.

Where can I study Law and Society?

There are a lot of wonderful programs and centers for studying law and society.

A non-exhaustive list of excellent universities with concentrations of law and society scholars where students can pursue graduate programs (these places also have excellent undergraduate programs) includes UC Berkeley‘s Jurisprudence and Social Policy program (general law and society program plus a Center—the Center for the Study of Law and Society), UC Irvine‘s Criminology, Law and Society program (a great mix of criminology and general law and society) plus there are a lot of law and society folks at the law school and around campus, University of Washington (multiple disciplines), Northwestern University‘s Sociology department, University of Minnesota‘s Sociology department plus others (particularly strong in the area of punishment and society), University of Massachusetts at Amherst‘s Sociology and Political Science departments (with Amherst College nearby, another great center), University at Buffalo (multiple departments and a Center—the Baldy Center for Law and Social Policy), Purdue University‘s Sociology Department, Stanford‘s Sociology Department (plus other centers and departments), UCLA’s Sociology Department, UC Santa Cruz (especially the Politics Department), and the University of Toronto‘s Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies (a mix of criminology and generalist law and society, bridging the US and Canadian fields) and the Sociology Department.

The Consortium for Undergraduate Law & Justice Programs maintains a list of undergraduate programs; not all of these are law and society in the sense described above, but they will be places where one can study law from various perspectives. The University of Hawaii at Mānoa also offers an undergraduate certificate in law and society (housed in the sociology and political science departments) and we have law and society scholars across campus (including at the law school).

While the above universities are great hot spots for law and society, law and society scholars are scattered throughout various departments around the world! But the best way to meet and interact with law and society scholars is to join one of the professional associations and/or attend their annual meetings!